Module 3: Collaborative Structure and Joint Ownership

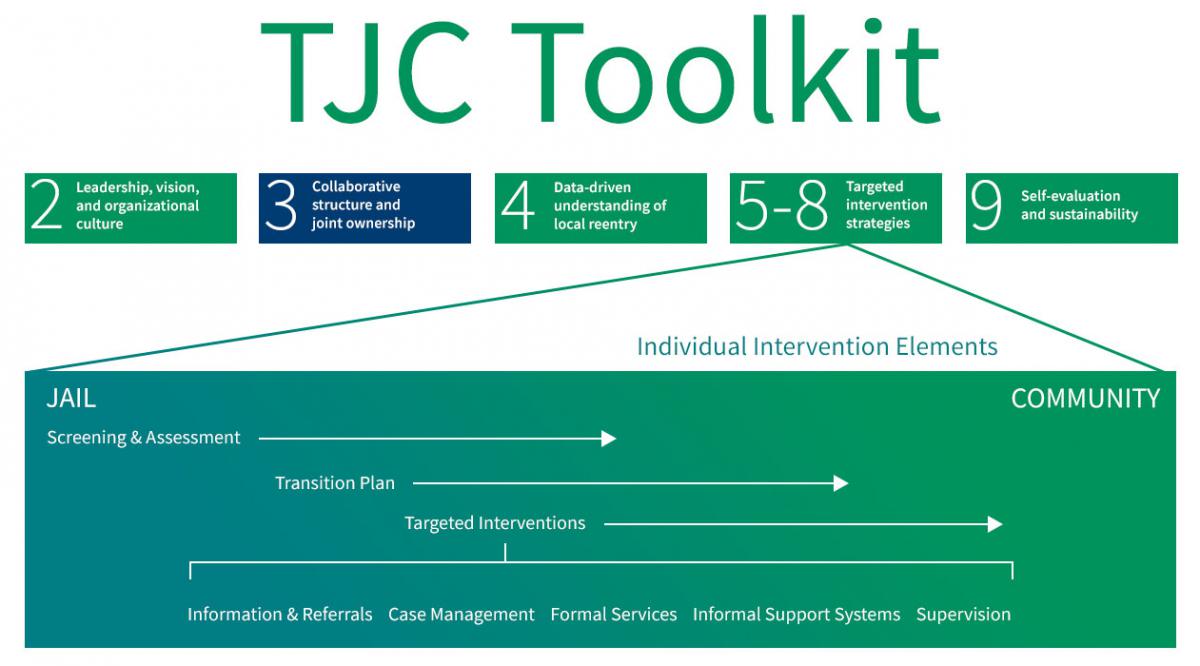

This visual indicates where Collaborative Structure and Joint Ownership fits in the Transition from Jail to Community model. It is one of five key system elements that must be in place for the TJC model to work.

Welcome to Collaborative Structure and Joint Ownership. This module is designed to provide practical information to assist you in developing a reentry system where collaboration and joint ownership permeate the transitional process.

A central component of the Transition from Jail to Community (TJC) model is that reintegrating individuals from jail to the community is the collective responsibility of both the jail system and the community. The transition process is too complex for one agency or organization to do alone. One agency cannot provide the range of services necessary to maximize opportunities for behavioral change. A systems approach to jail transition requires a collaborative structure that can secure participation from key partners, provide focus for the initiative, maintain momentum, and empower members of the collaboration.

“Collaboration has been challenging in building the reentry system in Denver; trying to get everyone on the same page is difficult when everyone (both public and private) has been doing their own thing for so long. However, the benefits have outweighed the negatives. Collaboration allows for multiple perspectives, experiences, and influences to enrich the services available to people transitioning from jail to community, and urges us to think through the impact of our work and our clients and all of our partners.”

Shelley Siman, Program Coordinator

Denver Crime Prevention and Control Commission, Denver, CO

Ask yourself what interventions are needed to address the barriers your jail population faces as they return to the community. Does your agency have the capacity and resources to address them all?

|

|

Effective transition strategies rely on collaboration and information sharing among jail- and community-based partners and joint ownership of both the problem and the solution. Given that many of the people who exit jails are already involved with multiple social services and criminal justice agencies, a collaborative approach is essential to tackling jail transition. In addition, the scarcity of resources to manage this large population demands such an approach to avoid duplication or conflict in the delivery of valuable interventions. This module has four parts and will take between 25 and 30 minutes to complete.

Recommended audience for this module:

|

|

Module Objectives

This module is intended to help you learn the key processes to collaborate across government, nongovernment, and community-based organizations. Such collaboration allows all parties involved to maximize the impact intended by the TJC model through shared understanding and aligned actions. It will also guide you in structuring your collaboration to oversee and complete the work of implementing the TJC model.

This module includes:

- Understanding the benefits of collaboration and joint ownership

- Identifying partnering agencies

- Determining each party's responsibilities

- Structuring your TJC collaborative

- Developing long-term partnerships with community agencies

There are four sections in this module:

- What Is Collaboration?

- Formalizing the Collaborative Structure

- Developing a Reentry Implementation Committee

- Terms Used in the Field

This module also includes templates, links, field notes, case studies, and other materials to help you expedite the process in your community and to highlight how TJC partnerships have developed across the country.

By the end of this module you will be able to do the following:

- Identify the diverse and multiple partners in your community including existing advisory committees.

- Coordinate a collaborative planning process.

- Organize a reentry implementation committee of partnering agencies.

- Develop shared goals and principles.

- Draw upon excellent work being done in the field.

Module 3: Section 1: What Is Collaboration?

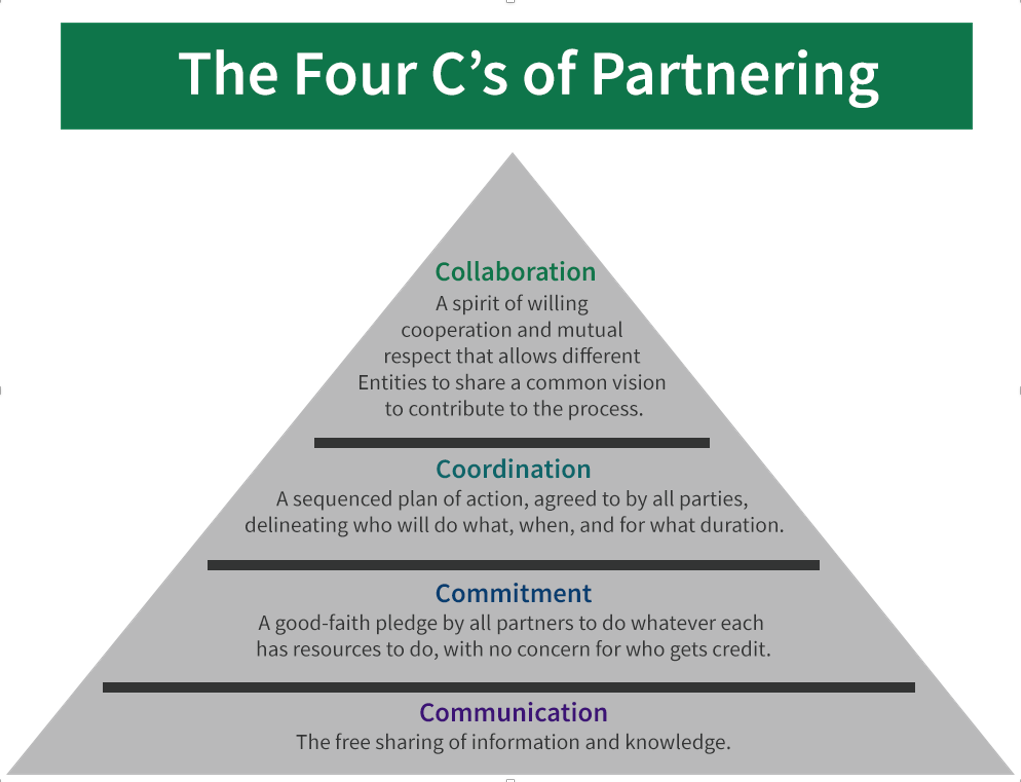

Collaboration is “a cooperative venture based on shared power and authority. It is nonhierarchical in nature. It assumes power based on knowledge or expertise as opposed to power based on role or function.” 1 If communication is the foundation of the partnering pyramid, collaboration is the pyramid's tip, with coordination and commitment squarely in the middle. 2

TJC Leadership Profile

Click here for a TJC Leadership Profile on Chester Cooper, Director of the Department of Community Corrections and Rehabilitation in Hennepin County, MN.

All four C's of partnering are important for the success of the TJC model, but collaboration must occur for the model's long-term success.

To see if you are ready to be part of a collaborative effort. You should be able to answer “Yes” to each statement below.

Are you ready for a collaborative effort? | Yes | Not Yet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I recognize that the agency I represent is mutually dependent on other agencies for the success of people leaving jails. | ||

| 2. | I and the agency I represent are willing to give up some authority/control for the TJC model to succeed. | ||

| 3. | I know that I will benefit and gain new knowledge when working together with outside agencies. | ||

| 4. | I understand that not everyone shares my perspective and I'm open to different views. | ||

| 5. | I am willing to commit my time and effort to making the TJC model work. | ||

| 6. | I am committed to suspending my judgment about what works to change individual behavior and will consider new information as I begin to collaborate with other system stakeholders. | ||

| 7. | I am committed to evidence-based decision making and am ready to change policies and practices that do not yield the best outcomes as defined by the TJC collaborative. | ||

Differences between Collaboration and Coordination

Though often used interchangeably, “coordination” and “collaboration” are distinct terms. Coordination is to “bring together disparate agencies to make their efforts more compatible.” 3

Collaboration, on the other hand, is “a cooperative venture based on shared power and authority. It is nonhierarchical in nature. It assumes power based on knowledge or expertise as opposed to power based on role or function.” 4

The outcome of a collaborative partnership is something new that harnesses the knowledge of multiple agencies to create a new model of reentry with an investment in shared authority, resources, and priorities for the common good.

1 Kraus, W. A. (1980). Collaboration in organizations: Alternatives to hierarchy. Human Sciences Press., p. 12.

2 North Carolina Department of Public Safety. (2009). North Carolina's serious and violent offender reentry initiative: Going home. A systemic approach to offender reintegration [PowerPoint slides]. SlidePlayer. https://slideplayer.com/slide/235085/

3 Robinson, D., Hewitt, T., & Harriss, J. (1999). Managing development: Understanding inter-organizational relationships. Sage, p. 7.

4 Kraus, W. A. (1980). Collaboration in organizations: Alternatives to hierarchy. Human Sciences Press., p. 12.

Summary

Now that you have completed this section, you understand the concept of collaboration that is used throughout this toolkit, and you recognize that collaboration involves the nonhierarchical sharing of power to achieve a greater good.

Module 3: Section 2: Formalizing the Collaborative Structure

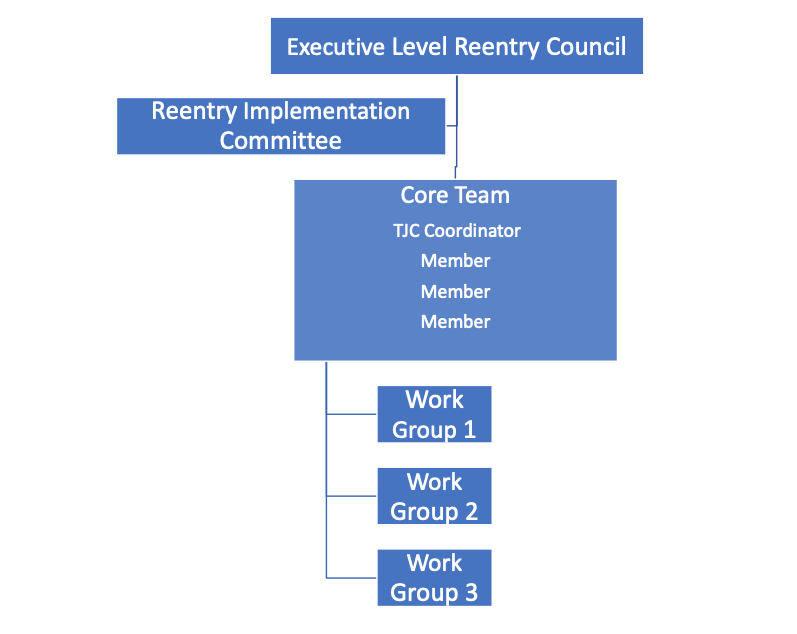

In this section we discuss how to formalize the collaborative structure. We doubt that any two locations will have identical collaborative structures, but often it is a pyramid-style structure comprising an executive-level reentry council or criminal justice coordinating council; a reentry implementation committee that includes a core-team group of members and subcommittees or work groups composed of system stakeholders with decision-making authority. Each group or agency will have its own unique role to play in the collaborative structure, and agencies may use documentation such as memoranda of understanding to formalize the collaborative process in writing.

Section 2: 1. Forming an Executive-Level Reentry Council

In many jurisdictions, the executive-level reentry council is initially charged with developing the organizational structure of the reentry implementation committee. This council should be composed of high-level individuals with decision-making authority such as sheriffs, county commissioners, city council members, jail administrators, judges, and officers of the court. They provide the jail-to-community reentry effort with broad strategic guidance, give it legitimacy in the jurisdiction through their support, and hold it accountable for meeting its goals and objectives. Many jurisdictions already have an executive-level reentry or criminal justice coordinating council or some other established body that can serve in this function. Adding the TJC Initiative, however, to the agenda is essential to realize the collaborative TJC goals discussed in this module.

Responsibilities of the executive-level reentry council include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Championing the initiative in the community.

- Serving as a vehicle for community-wide communication.

- Selecting members of the council's committees and subcommittees.

- Holding the initiative accountable for meeting performance measures.

- Setting policy for the TJC initiative.

- Identifying macro-level evaluation components.

- Evaluating and, as necessary, changing or modifying individual organizational policies and/or practice to accommodate the attainment of agreed upon TJC goals and objectives

Section 2: 2. Forming a Reentry Implementation Committee

The reentry implementation committee is a central team of individuals who oversee the detail-oriented work of devising and implementing the jurisdiction's TJC strategy. The implementation committee needs to have an active and committed membership to carry out its work. Members of the implementation committee must have the full support of executive-level TJC partners. The implementation committee must also take responsibility to maintain communication with TJC executive-level partners to maintain system-level continuity of the TJC implementation effort and/or gain approval for necessary change(s).

Knowledge and ability to make a time commitment may be more important than formal position in selecting committee members. In some jurisdictions, members of the executive council will meet to recommend implementation committee membership. Some of the members may come from the reentry working groups (although they may be too busy to make the necessary commitment), whereas others will be from the greater stakeholder community. In other jurisdictions, the implementation committee is convened prior to the executive-level reentry council.

Responsibilities of the reentry implementation committee may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Meeting at least monthly.

- Communicating regularly with the executive-level reentry council to keep them fully informed on the progress of the TJC initiative.

- Providing recommendations to the executive-level reentry council on important decisions in the design and implementation of the initiative.

- Developing goals, outcomes, and measures for the TJC initiative.

- Convening and overseeing work groups to address specific implementation issues.

- Identifying what entity or person will complete these tasks.

- Providing clear timelines and deadlines for the tasks in the prior bullet points, and monitoring progress against them.

See Task 2 (Collaboration Structure and Joint Ownership) in the TJC Implementation Roadmap to see a to-do list of the tasks and subtasks needed to create and implement a collaborative structure. Review Collaboration Structure and Joint Ownership of the TJC Implementation Roadmap to see a to-do list of the tasks and subtasks needed to create and implement a collaborative structure.

Consider inviting the jail's TJC reentry coordinator (e.g. point person), mental health providers, defense attorneys, community shelter staff, educators, community corrections officers, housing authority staff, the district attorney's office, victim's advocates, health care providers, employment specialists, people from the faith community, and other social service providers to serve on the reentry implementation committee.

Section 2: 3. Core Team

An effective core team is an integral part in the success of implementing TJC in your community. Unlike the executive-level reentry council and the larger reentry implementation committee, the core team is the key mechanism for sharing day-to-day leadership of the TJC effort. This small group of people work closely with the designated TJC coordinator who is championing the TJC model in your community to monitor progress, identify priority tasks, and carry them out. Core teams create multiple keepers of the “big picture” regarding the TJC strategy and increase the ability of sites to make necessary change(s) in multiple agencies to realize system-wide progress in TJC implementation. The most effective core teams include people from different agencies, representing both criminal justice and community spheres, who contribute varied perspectives and knowledge bases to TJC implementation planning.

Section 2: 4. Work Groups

A responsibility of the reentry implementation committee is to convene and oversee work groups tasked on specific implementation issues. Volunteers for these working groups can come from the reentry implementation committee membership or from key players outside the committee who have the skill set, subject expertise, and the interest in completing these tasks.

For example, a community provider with expertise in correctional programming may be involved in a curriculum development subcommittee but may not be on the reentry implementation committee. Work groups will complete concrete, discrete tasks delegated to them by the reentry implementation committee. The committee should give them clear, written directives with defined end products; the committee should bring its results to the executive-level reentry council for review and approval.

Experience from the TJC Phase 1 learning sites informs us that working groups are most efficient when they are assigned a specific purpose, accomplish their assignment, and then disband with the understanding that the group can be renewed whenever appropriate. Each working group automatically expires after 12 months, unless the reentry implementation committee determines the group should continue.

Click here to see the responsibilities, list of members, and invitees of the Howard County, Maryland, TJC Organizational Structure.

Section 2: 5. Memoranda of Understanding

The success of the reentry implementation committee will depend more on what responsibilities participating agencies accept rather than what they are obligated to contribute. Nevertheless, though normally not legally binding, formalizing the process by drafting a memorandum of understanding (MOU) expresses a long-term commitment to the process and adds a sense of credibility and professionalism to the reentry collaboration.

Other benefits of an MOU:

- Facilitates communication by defining a process for regular meetings, phone contact, or data exchange.

- Protects both parties against differing interpretations of expectations by either party by spelling out details of the relationship.

- Enhances the status of the case management agency in the community through formalized relationships with established or influential agencies.

- Reduces friction over turf issues by specifying responsibilities.

- Transfers authority to perform a mandated function from one agency to another or from one level of government to another.

- Creates a clear and formalized agreement to move forward and partner together.

- Specifies services for a provider agency to provide to clients and ensures that said services have continuity with services provided by other TJC partners.

- Specifies the type of clients appropriate for the case management agency and how referrals should be made.

- Cuts through red tape by defining new or altered procedures for clients.

Formal Linkages

In many small jurisdictions, resources are limited and populations are often too small to warrant funding or attention for programming and other transition efforts. To enhance their ability to perform justice system functions effectively, many local governments enter into formal agreements to pool their resources and populations. Such intergovernmental collaboration demonstrates information-sharing commitment and the potential to sustain TJC efforts.

Sections of an MOU:

- Purpose or goal of the collaboration or partnership and its importance relative to realizing system-wide TJC goals.

- Key assumptions

- Operating principles or statement of agreement

- The name of each partnering agency

- Each partner's responsibilities under the MOU

- Effective date and signatures

Jails, governmental agencies, and community-based organizations may need to develop formal linkages with each other outside of the reentry implementation committees' MOU. Linkages would include agency-to-agency formal agreements with probation and public health departments, community health centers, community mental health centers, drug treatment programs, STD counseling and test sites, tuberculosis clinics, Medicaid offices, HIV infection services, one-stop workforce centers, housing providers, and service providers presently working with those transitioning from jail to the community.

Information Sharing

MOUs or other information release forms are essential when developing structures for information sharing and service coordination among providers and between providers and the facility. The most common reason for poor information sharing is confusion or misperceptions around what agencies are allowed to share while enforcing privacy policies and requirements. The TJC initiative recommends implementing formal guidelines for the following purposes:

- Referring incarcerated individuals to community providers.

- Informing providers about the release of relevant individuals. For example, those with a history of homelessness and mental illness.

- Sharing release plans with providers.

- Developing systems for sharing information, such as electronic databases or regular meetings among providers.

For more information and examples from the field:

- Crayton, A., Ressler, L., Mukamal, D., Jannetta, J., & Warwick, K. (2010). Partnering with jails to improve reentry: A guidebook for community-based organizations. Urban Institute.

- Ervin, S., & Gulaid, A. (2022). Safety and justice challenge case study: Using cross-system collaboration to reduce the use of jails implementation lessons from East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, the city and county of San Francisco, and St. Louis County, Missouri. Urban Institute.

- Justice Management Institute [JMI]. (2023). National Network of Criminal Justice Coordinating Councils (NNCJCC) resources. https://jmijustice.org/national-network-of-criminal-justice-coordinating-councils-nncjcc-resources/

- Cushman, R. C. (2002). Guidelines for developing a criminal justice coordinating committee. National Institute of Corrections.

- Davidson County, TN. (n.d.). Faith-based jail to the community work group statement of purpose with measurable short and long term goals.

- San Diego, CA. (2012). San Diego Reentry Roundtable Overview.

- Howard County, MD. (2013). TJC organizational structure.

- Douglas County (KS) Sheriff's Office. (2017). Reentry programs. This document highlights reentry-related programs at the jail, acknowledges staff from the jail and community by name for their work, etc.

- Charleston County (SC) Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. (2024). https://cjcc.charlestoncounty.org/

Organizational Chart Examples

- Denver, CO. (2009). Initial organizational chart, and working group outcomes explaining early TJC initiative structure and responsibilities (Large jail example).

- Kent County, MI. (2009). Initial organizational chart explaining early TJC Initiative Structure (Medium/large jail example).

- La Crosse County, WI. (n.d.). Initial organizational chart and mission explaining early TJC Initiative structure (Medium/large jail example).

- San Diego, CA. (n.d.). San Diego County TJC Initiative Structure. (Large jail example).

Memorandum of Understanding and Partnership Agreement Examples

- Denver, CO. (2009). Initial organizational chart, and working group outcomes explaining early TJC initiative structure and responsibilities (Large jail example).

- Kent County, MI. (2009). Initial organizational chart explaining early TJC Initiative Structure (Medium/large jail example).

- La Crosse County, WI. (n.d.). Initial organizational chart and mission explaining early TJC Initiative structure (Medium/large jail example).

- San Diego, CA. (n.d.). San Diego County TJC Initiative Structure. (Large jail example).

Summary

Now that you have completed this section, you understand the process to formalize a collaborative structure through a pyramid-style structure composed of an executive-level reentry council, reentry implementation committee, and work groups. You also recognize that it is essential to define clear roles and responsibilities of TJC stakeholders, formalized through memoranda of understanding, when necessary, to implement the TJC model efficiently and realize maximum benefit of TJC efforts and practices within your jurisdiction.

Module 3: Section 3: Developing a Reentry Implementation Committee

In this section you will learn in more detail how to develop a reentry implementation committee made up of public and private agency and community-based organization representatives to increase the success of the Transition from Jail to Community model.

In most communities, agencies and organizations are already providing services to the criminal justice population. The issue is to what degree these services are being provided in a coordinated and collaborative way. This section will guide you through the development and promotion of a multidisciplinary reentry implementation committee, including jail staff, other criminal justice and human service agencies, and community-based organizations. A reentry implementation committee will allow your jurisdiction to jointly craft and carry out a jail-to-community transition strategy that maximizes the impact of available resources, improves individual outcomes, saves money, and delivers long-term public safety. The TJC implementation committee will also serve as a liaison between TJC stakeholders and work groups and executive-level leadership to ensure continuity and adherence to overarching TJC goals obtained collaboratively.

The development and implementation of a reentry implementation committee requires the following important steps:

1. Select a TJC coordinator

2. Identify partnering agencies and interested stakeholders

3. Reach out to earn partner support

4. Convene the partnering agencies

5. Identify shared goals, principles, and outcomes of interest

6. Write a mission and vision statement

7. Document partner agencies' resources and gaps

8. Develop common performance measures

The following sections discuss these 8 steps, though modules Data-Driven Understanding of Local Reentry and Self-Evaluation and Sustainability also discuss steps 7 and 8.

Section 3: Step 1: Select a TJC coordinator

Identifying a TJC coordinator in your agency or the community with the clout, independence, and fortitude to bring the right people together is the first step in the partnering process. A local reentry champion of the TJC model, such as the sheriff or the county commissioner, will select a coordinator and give him or her total support and cooperation to move the process along as well as some policy-level decision making authority. This person must have the necessary time to devote to moving this complex effort forward. The coordinator can be from a jail, the courts, probation, or a community setting; there is no one job title, position, or training experience needed to play this role. Determining the right person is dependent on local politics, history, and personalities. 1 Often it is based on which organization has money for this position or is willing to add these duties as part of someone's job.

Think about what characteristics you are looking for in this person:

- Committed to the TJC model.

- Knowledgeable about the risks and needs of people transitioning from jail to the community.

- Interested in understanding current research or best practice.

- Personable, well organized, and a communicator with strong listening skills who has the ability to facilitate collaborative meetings among identified TJC stakeholders.

- Has the clout to get things done.

- Knows the community and its stakeholders.

- Respected by both internal and external staff of his/her home organization.

- Understands current reentry policies and practices throughout the local community.

- Open to understanding TJC stakeholder organizational cultures and values and collaborating with partner agencies to develop policies and practices that are recognized beneficial to the TJC model.

- Believes in the capacity of incarcerated people to change as a result of agreed upon services provisioned by TJC stakeholders throughout the TJC system of reentry.

Section 3: Step 2: Identify partnering agencies and interested stakeholders

Identifying partnering agencies and community leaders is a key component to the success of the TJC model. You will find that some will be government agencies, but the majority will probably be agencies providing services at the local level. The long-term goal is for the agencies to form a coordinating reentry council,so including the right agencies and the appropriate agency representative is essential.

The spectrum of your possible collaborators is wide open:

Key stakeholders include:

- Jail administrators or sheriffs

- Police departments

- Community supervision and pretrial services agencies

- The courts, prosecutors, and public defenders

- County executives and local legislators

- City officials

- Treatment and social service providers

- Health and mental health agencies

- Housing, economic development, and workforce development agencies

- Local businesses and corporate entities

- Victim advocates

- The formerly incarcerated and their families

- Community residents

- Faith and community-based providers

- Veterans Affairs

Partners

Don't forget to include victims' advocacy groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD). Part of the long-term healing process for many victims and their families is knowing that incarcerated individuals may become productive members of society.

They want incarcerated individuals to be held accountable for their actions when they return home. These groups recognize the importance of providing reentry services to facilitate their successful reintegration. You might be surprised at the level of cooperation you'll receive from victims' rights groups. It is also important to include the formerly incarcerated in this process, because they understand firsthand the barriers and problems facing this population. Those involved in this effort should be incarcerated individuals with a long-standing record of doing well after release and not those newly released.

Here is how to start:

Begin by making a list of all the government and nongovernment agencies and community-based organizations your agency presently works with to help transition people from jail to the community.

- In Montgomery County, Maryland, the Department of Labor has set up a One-Stop Center in the jail. This allows the jailed individuals to get the necessary job search and development skills needed prior to being released from the facility.

Next, identify any other government and nongovernment agencies and community-based organizations that have contacts with the jail population pre- or post-release but which are not formally engaged in the transitional process.

- Police in your community may drop off suspects for processing at the jail's booking site but may not have any formal collaboration with the jail.

Finally, identify the government and nongovernment agencies and community-based organizations that play a key role in meeting the risks and needs of the returning population but have no connection to the jail.

- The local community health care system often doesn't have a relationship with the jail.

Field notes from Kent County, Michigan

“We recently created an organizational structure allowing us to meet frequently with other local community-based providers, and local and state supervision agencies that share our broader mission for a safer community. These reentry committee meetings spawned action, innovation, and joint projects, and it has resulted in energizing Kent County's reentry efforts. The Sheriff's Office has always been on good terms with groups such as pretrial services, Friend of the Court, public schools, community corrections, homeless advocates, treatment centers, probation and parole, and in the past, we have periodically cooperated on individual projects. When we purposefully aligned ourselves with the mutual goal to address our common public safety interests in attacking the barriers to successful offender reintegration, we began to fully realize the many benefits of this level of collaboration.”

—Captain Randy Demory

Sheriff's Department and Chair of the Community Reentry Coordinating Council (CRCC)

Field note: Denver Crime Prevention and Control Commission Membership (2024)

Office / Constituency | City Connection | Name/ Delegate | Ordinance Appointment |

| Office of the Mayor | Mayor | Mike Johnston/ Evan Dryer | Appointment by Position |

| Department of Human Services | Head of Human Services | Anne-Marie Braga/ Mimi Scheuerman | Appointment by Position |

| Department of Public Safety | Executive Director of Safety | Armando Saldate / Jeff Holliday | Appointment by Position |

| Denver Police Department | Chief of Police | Ron Thomas | Appointment by Position |

| Denver Sheriff Department | Sheriff | Elias Diggins | Appointment by Position |

| Denver County Court | Presiding Judge | Judge Carrie Lombardi | Appointment by Position |

| City Attorney’s Office | Head Attorney | Kerry Tipper/ Marley Bordovsky | Appointment by Position |

| Office of the Municipal Public Defender | Chief Municipal Public Defender | Colette Tvedt / LeAnn Fickes | Appointment by Position |

| Community Corrections, Department of Public Safety | Director of Community Corrections | Greg Mauro | Appointment by Position |

| Denver Department of Public Health & Environment | Manager | Karin McGowan | Appointment by Position |

| Colorado Department of Corrections | Director of the Division of Parole | David Wolfsgruber | Appointment by Position |

| Denver County Court Adult Probation Department | Chief Probation Officer | Cary Heck, PhD | Appointment by Position |

| Denver County Court Probation Department | Chief Probation Officer | Yessenia Guzman | Appointment by Position |

| Office of the Colorado State Public Defender | Head of Denver Office | Blake Renner | Appointment by Position |

| Office of the Denver District Attorney | District Attorney | Beth McCann | Appointment by Position |

| City Council | City Council Representative, District 6 | Paul Kashmann | Appointment by Position |

| City Council | City Council Representative, District At-large | Sarah Parady | Appointment by Position |

| City Council | City Council Representative, District At-large | Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez | Appointment by Position |

| Colorado Criminal Defense Bar Private Practice Attorney | Sean McDermott | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Provider of Services with Evidence-Based Criminal Justice Policy and Practices | VACANT | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Denver Public Schools Leadership Team Representative | VACANT | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Juvenile Justice System Representative | Jonathan McMillan | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Juvenile Justice System Representative | Judge Laurie Clark/ Magistrate Lisa Gomez | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Academic Knowledgeable about Evidence-Based Criminal Justice Policy and Practices | Laura Rovner, PhD | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Behavioral Health Services Representative | Jennifer Gafford, PhD | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Homeless Service Providers Representative | Lisa Thompson | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Criminal Justice and/ or Crime Prevention Community Org and/ or Victim Representative | Thomas Hernandez | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Criminal Justice and/ or Crime Prevention Community Org and/ or Victim Representative | Kara Napolitano | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Criminal Justice and/ or Crime Prevention Community Org and/ or Victim Representative | VACANT | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Denver Community At-large | VACANT | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Denver Community At-large | Orlando Salazar | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Denver Community At-large | Anthony Pfaff | Citizen Appointment by Mayor | |

| Previously Justice-involved Representative | Tajuddin "Taj" Ashaheed | Citizen Appointment by Mayor |

In step 2 you identified community partners and collaborators who have a direct or indirect role transitioning people from jail to the community. It is now time to begin a dialogue by reaching out to government and nongovernment agencies and community organizations to determine their interest in being part of a TJC partnership.

The following steps will help you maximize the chance that they say “yes.” First, do your homework before you pick up the phone. Print a checklist for preparing to reach out to potential partners. Remember your goal is to develop a long-term relationship built on trust and respect. This takes time, so don't rush it.

Participation Interest

Many community stakeholders, particularly service providers, will be interested in being involved in a reentry initiative, though not all will want to provide services for jailed individuals. That is okay, and you should tell them that it is not a requirement to participate. More important is ensuring that their efforts to serve the reentry population in the community are coordinated with what is happening with these individuals in the facility and with the work of other service providers in the community. The key here is to coordinate efforts to meet their goals.

Phrases you might want to use during your conversation:

- Would you like to build a safer community by partnering with us as part of community-wide transition from jail to the community initiative?

- We can’t afford to do business the way we have been doing it.

- We need a coordinated effort to solve the problem. We can’t do it alone.

- We need to pool our resources in a more strategic way.

- We need to pool resources and coordinate our efforts.

- Partnering will improve outcomes for both incarcerated people and our organizations.

Next, set up the first communication. Click here for more details.

Remember that you may need a follow-up conversation by phone or e-mail before you think they are ready to commit to the TJC process.

Finally, invite them to a meeting:

- Tell them you are organizing a reentry implementation committee and would like them to be a part of it.

- Determine what is a good day and time for them to meet.

- Find a neutral location that is convenient for everyone.

- If possible, provide food for the first meeting.

- Use free online scheduling and conference web sites to help find a date on which everyone can agree.

Field notes from Santa Barbara County, California

“I’m a retired business executive from Silicon Valley. I think it is important for private citizens to initiate, and be involved in, efforts like this because we are often able to help break down the barriers that exist in the various bureaucracies. Initially I went to a number of county and state officials. I then asked each of them if [reentry] was really a problem and would they be interested in helping to build a solution. Every single one said ‘yes’ and ‘yes.’ That started us on the process.”

—Rick Roney, Chair

Santa Barbara County, CA, Reentry Committee

Section 3: Step 4: Convene the partnering agencies

The first goal, after you have earned their initial support, is to bring the multiple stakeholders together, preferably over breakfast or lunch, to brainstorm about transition challenges in your community and how to develop an oversight reentry committee to oversee and guide the TJC process.

The length and content of the agenda will depend on how much time you have at the initial meeting. The first TJC meetings in Lawrence, Kansas, and Denver, Colorado, each lasted two days, whereas other communities scheduled an hour for the first meeting. Regardless, at some point early in the TJC implementation process, whether during an initial meeting or soon afterward, significant time should be committed to developing a local TJC Model that is clear to all participants and includes shared system-wide goals and practices.

Inclusiveness

A question that always comes up is, “How inclusive should the coordinating reentry committee be?” Do not feel pressured to convene a large group at first. It is difficult to accomplish anything with 20 people at the table, representing different interests and different agendas; although Philadelphia had 44 members on its reentry committee and it worked for them.

It often makes sense to start off small. If people ask why their agency was not invited—because word will get out—just say the decision was to start with the agencies and providers who have the most direct contact with those released from jail in the 30 days after release, but the reentry committee looks forward to involving all parts of the community eventually. Many other agencies can be involved on subcommittees and work groups on specific topic areas as the project moves forward.

Here is how to begin:

- Welcome everyone to the meeting and briefly introduce yourself.

- Pass out a printed agenda, which you e-mailed to participants in advance.

Click here – Agenda Template - Explain why they are here: goals and organization of the TJC meeting.

- Use an icebreaker to help the participants get to know each other and feel more comfortable. Click here – Icebreaker examples

- Discuss what jail transition looks like in your community.

- Introduce the TJC model.

Click here – TJC model - Discuss what their expectations are for the meeting.

- Discuss what issues they would like to address during the meeting.

- Get specific: ask them to begin developing the mission and vision statement or discuss the barriers they see with transitioning people from the jail to the community.

Mission statement example:

Mission Statement, Douglas County, KS

The Douglas County Corrections Division mission is to provide safe, secure, humane, and legal treatment for all inmates through direct supervision management concepts while fostering a safe and successful transition through interventions, programs, and services from the facility into our community. - Ask the participants if they can meet once a month until there is a consensus on how a coordinated and collaborative reentry strategy can be accomplished in their community.

- Discuss the importance of reentry implementation committees and work groups.

- Ask for volunteers for each committee.

- Before the meeting adjourns, take the time to ask the partners to help you identify key roles, knowledge, and skills not represented in the current partner group. Ask them to name additional partners to bring in the missing elements identified. You will want to update your partner list every six months as implementation progresses.

- Make sure to finish with concrete next steps, people assigned to accomplish them, or a next meeting scheduled. It’s important for new partners to leave with a sense that they have accomplished something and to have a clear understanding of how and when the work they’ve begun will continue.

Section 3: Step 5: Identify shared goals, principles, and outcomes of interest

“It’s very hard to get things accomplished if you haven’t worked on structure and getting people on board before you proceed.” ---TJC stakeholder

In the beginning, developing shared goals, principles, and outcomes of interest will be the main work of the reentry implementation committee. Start by creating a timeline of what needs to be accomplished.

Review the TJC Implementation Roadmap for a to-do list to help get you started:

Identifying an Organization’s Level of Power and Interest in the Context of the TJC Model

Drawing a stakeholder grid is an excellent exercise to identify local leaders, their relationship to the system, their interest, their power to affect system actions, and their alignment with the TJC model. In essence, you are teaching key stakeholders how to have this discussion at the system level while gauging interest or authority to implement or block change.

Your goal is to engage stakeholders through a variety of exercises and actions outlined in previous sections and then identify the level of power and interest each organization and agency has in transitioning people from jail to the community. This is a useful exercise to assist in systems-level discussions and to understand various influential leaders who exist within your system.

Below is an example of a stakeholder grid. We have listed different stakeholders below. Think where each one of them fits in your jurisdiction.

|

|

Stakeholder Power/Interest/Influence Grid

There are four squares in a stakeholder grid:

- Keep Satisfied: Stakeholders who fall within this square are those who have a lot of power to influence criminal justice system practice or change, but have little interest in changing anything.

- Manage Closely:Stakeholders who fall within this square are those who have a lot of power to influence criminal justice system practice or change and have a lot of interest in or desire to change current criminal justice practice to obtain improved outcomes.

- Monitor:Stakeholders who fall within this square are those who have little to no power to influence criminal justice system practice or change and little to no interest in changing anything.

- Keep Informed:Stakeholders who fall within this square are those who have little to no power to influence criminal justice system practice or change; but have a lot of interest in or desire to change current criminal justice practice to obtain improved outcomes.

By doing this exercise in a group setting, one can identify the organizations that have a high interest and power in the TJC model and learn what motivates them, while also identifying those organizations with low interest. It is extremely important to note that no stakeholder should be excluded from participating in TJC implementation activities because of their levels of interest or power.

The purpose of this exercise is to understand the different motivators for and against change within your system and to allocate resources and make determinations relative to communication and engagement strategies. Accordingly, dialogue should ensue about what it takes to engage people within the TJC effort, from empowering the low-interest and low-power organizations to understanding and managing differences that high-power stakeholders have with the TJC approach.

Drawing a Stakeholder Grid

First, ask your group to rate each of the stakeholders by their effect on transitioning people from jail to the community on a scale of 1 (least) to 10 for the following:

- Power/Influence

- Interest

Based upon these ratings, plot each of the stakeholders on the Stakeholder Power/Interest/Influence Grid. Bryson (2003) lays out seven points of constructing a Stakeholder Grid: 2

Whole team:

- “Tape four flip chart sheets to a wall to form a single surface two sheets high and two sheets wide.

- Draw the two axes on the surface using a marking pen. The vertical axis is labeled interest, from low to high; while the horizontal axis is labeled power, from low to high.

- Planning group members brainstorm the names of stakeholders by writing the names of different stakeholders as they come to mind on a 1×1 inch or 1 x ½ inch self-adhesive label, one stakeholder per label.

- Guided by the deliberations and judgments of the planning group members, a facilitator should place each label in the appropriate spot on the grid.

- Labels should be collected in a round-robin fashion, one label per group member, until all labels (other than duplicates) are placed on the grid or eliminated for some reason.

- Labels should be moved around until all group members are satisfied with the relative location of each stakeholder on the grid.

- The group should discuss the implications of the resulting stakeholder placements.”

Section 3: Step 6: Write a mission and vision statement

“Vision without action is a daydream. Action without vision is a nightmare.” 3

This Japanese proverb sums up the importance of taking the time to develop a mission and vision statement. The mission and vision statement needs to appeal to all your constituents.

“Once well-intentioned system stakeholders take the time to examine their differences and similarities relative to local criminal justice practice and outcomes, they invariably realize that they all have in common one overarching desire: to do things as efficiently and effectively as possible to realize best outcomes and effects on long-term public safety. When such a realization occurs and a shared mission is developed, the positive effect that an aligned group of stakeholders can have on criminal justice outcomes, and thus public safety, is enormous.”

Gary Christensen, Former Chair

Dutchess County Criminal Justice Council

Dutchess County, NY

Vision Statement

Begin by drafting a vision statement. As you recall, the Leadership, Vision, and Organizational Culture module covered creating a vision for your organization. If needed, go back to this module and review Section 3: Creating a Vision. The vision statement for your collaborative structure should focus on the broad goals of the reentry implementation committee and clearly explain the following:

- Defining the reentry committee.

- The guiding philosophy behind the council’s formation.

- Goals of the of the reentry committee.

- Value the reentry committee adds to the community.

- Outcomes of a successful reentry committee.

Ask yourself the following questions when developing the vision statement:

- Which populations are your highest priority?

- What programs, services, and support do you want to provide to them?

- Where does reentry take place and for what duration?

- Who are the partners in the community—including government agencies, nonprofits, and the business community—that could play a helpful role in your reentry strategy?

- How will you measure your success?

Dutchess County, New York’s Criminal Justice Council Vision Statement:

“The Criminal Justice Council has become a system where the overriding concern is for the fair, equitable, cost-effective and efficient administration of justice for the immediate and long term; preventive programming is being developed to minimize entry and re-entry into the criminal justice system; planning is system based with goals and outcomes; decisions are grounded in information, research and facts, not politics; all Criminal Justice Council members are committed to actively work together to achieve this goal.”

Mission Statement

The reentry implementation committee’s mission statement is more concise and concrete than the vision statement. In a paragraph you will want to

- State the purpose for developing a reentry committee.

- Describe what the reentry committee plans to achieve.

- Explain the reentry committee’s commitment to transitioning people from jail to the community in the most effective and efficient manner.

- Describe the commitment to evidence-based policy and practice and how this commitment will result in the continual improvement of criminal justice practice.

Remember that long-term public safety is always the main priority, so a good mission statement not only states the purpose, but also addresses how it can be accomplished. For example, reduce recidivism by preparing incarcerated individuals to make a successful transition back to the community.

Kent County, Michigan, Community Reentry Coordinating Council's Mission Statement:

“To promote public safety by assembling a group of collaborators representing local agencies and entities who will work to identify, reduce or eliminate the barriers to successful community reentry for those citizens who were formerly incarcerated.”

Listed below are questions to think about:

What is the reentry implementation committee's mission?

- Protect the public

- Efficiency and cost-effectiveness

- Rehabilitation

- Support successful transition to the community

- Provide good in-jail treatment programs that offer ties or continuity with community-based resources

- Facilitate the linkage of individuals to services

- Collaboration and cooperation with partnering agencies

How does the reentry implementation committee plan to operationalize its mission?

- Intake and assessment

- Classification and housing assignment

- Transition plans for high-risk populations

- Treatment programs as appropriate

- Continuity in community

Section 3: Step 7: Document partner agencies' resources and gaps

One of the first priorities of the reentry implementation committee is to identify the present resources (financial, human, and technical) in place to support the TJC model. You need a picture of how people move through the jail, from intake to discharge, and the transition back to the community. In the next module, Data-Driven Understanding of Local Reentry, we discuss in depth how this is accomplished.

Section 3: Step 8: Develop common performance measures

The purpose of this step is to describe to you common performance measurements that will help the reentry implementation committee maintain accountability for its goals. See Performance Measures in the Self-Evaluation and Sustainability module for a comprehensive discussion on this topic.

For more information and examples from the field

1. Cushman, R. C. (2002). Guidelines for developing a criminal justice coordinating committee. National Institute of Corrections. CJCC’s have a broader scope than a reentry council, but the guidance is applicable for developing a cross-agency, cross sector collaborative structure.

- Council of State Governments Justice Center. (2005). Report of the Re-Entry Policy Council: Charting the safe and successful return of prisoners to the community focuses on planning a reentry initiative and is very detailed and helpful.

- Missouri Reentry Process (MRP) Local Team Starter Kit. (2006). A great source to read before you develop and host your first reentry council meeting. This 23-page reentry council starter kit provides easy-to-use tools, ideas, and suggestions on facilitating your meetings and discussions. The appendix is particularly helpful, including such items as minutes and outcome templates and brainstorming tools.

- Montero, G. (2007). Mapping the universe of reentry. The New York City Discharge Planning Collaboration. This report discusses how a group representing nearly 40 organizations with a stake in transitional planning came together to form the collaboration.

- New York City Jail Reentry Project Organizational Survey. (n.d.) This survey can help your community gain a better understanding of the collaboration and coordination of organizations; what the positive and negative concerns may be; and what kinds of relationships work best.

- American Probation and Parole Association, (1996).Restoring hope through community partnerships: The real deal in crime control. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments Published by the American Probation and Parole Association, Lexington, Kentucky. This handbook is one of the best guides on developing community outreach, with many examples and templates.

TJC Learning Site Examples

- Douglas County (KS) Sheriff’s Office. (2009). Sample TJC executive council agenda and minutes for small jurisdictions.

2. Douglas County (KS). (n.d.). A detailed list and description of TJC partner organizations.

3. Kent County (MI). (n.d.). TJC stakeholder contact information.

4. Kent County (MI). (n.d.). A detailed list and description of TJC partners, their resources and contact information.

5. San Diego (CA). (2013, February 12). The San Diego Reentry Roundtable overview: A detailed listing of the collaborative partners participating in the San Diego County, CA TJC initiative.

Summary

Now that you have completed this section, you should understand the steps you need to take to initiate a reentry implementation committee. You understand that you will need to identify a TJC coordinator, who has institutional clout and a “can do” attitude. You have tools to identify potential partner agencies, both from the agencies with which you are working and from other agencies. You can describe the structure of your first TJC meeting, and you recognize the importance of sharing goals, principles, and outcomes of interest. You know how to develop a mission statement to describe the purpose of TJC and detail what you hope to achieve.

Module 3: Section 4: Incorporating People with Lived Experience in Your Reentry Work

The leadership role of people who have experienced incarceration in reentry efforts has grown tremendously and continues to expand. The understanding that comes from such lived experience is an important contributor to the design and refinement of all aspects of your jail transition strategy, helping to ensure that it takes into account how reentry and change processes look and feel from the perspective of those experiencing them. People who share common experiences can also build trust and credibility more quickly with people who are engaged in your reentry programming. Finally, making people who have themselves experienced incarceration part of your jail transition partnership demonstrates foundational values to TJC: belief in change and understanding that people returning from jail are part of our communities.

This section will provide an overview of different ways that people with lived experience can be part of your TJC strategy. These roles are not mutually exclusive, and the list is by no means exhaustive. But it does provide different examples of the types of involvement that occur in jail reentry efforts around the country.

Some basic guiding principles a TJC collaborative should bear in mind as they partner with people with the lived experience of incarceration include:

- Recognize people’s expertise.

- Compensate them for their time as appropriate.

- Be ready to listen. Part of the importance of including people with this experience is they have different perspectives than system actors.

- Identify policy barriers to participation of people with lived experience and see if you can reduce them.

- Build in opportunities for self-care, as those with lived experiences will work in spaces that could remind them of past trauma.

Participation in Collaborative Structure

A critical aspect of involving people with the lived experience of jail incarceration in your TJC efforts is intentional inclusion in the collaborative structure. This ensures their perspective is informing the development and refinement of your TJC strategy. This is a practice the first TJC demonstration sites were doing over a decade and half ago.

Such inclusion can involve designating a seat in collaborative bodies, as Denver’s Crime Prevention and Control Commission does by specifying that at least one member must be justice-involved. Deliberate recruitment of organizations led by formerly incarcerated people into your reentry collaboration can also serve this purpose. It’s also important for the partnership and its members to consistently support people with lived experience in their participation, as the power differential between them and appointed members who lead government agencies can inhibit truthful conversation.

A potential pitfall to avoid is putting one or two people with relevant lived experience in the position of having to represent the diversity of views and specific experiences among all the people who have been incarcerated in the jail. Finding ways to involve a broader array of people with lived experience in the effort can address this concern. Some jurisdictions stand up entities specifically composed of people with lived experience to advise and guide their reentry efforts, as Santa Clara County did with its Reentry Lived Experience Advisory Board(LEAB).

Peer Support

Peer support is an approach the leverages shared experience to support behavior change and is a particularly common aspect of mental health and substance use disorder interventions. SAMHSA articulates the value of peer support in this way:

This mutuality—often called ‘peerness’—between a peer support worker and person in or seeking recovery promotes connection and inspires hope. Peer support offers a level of acceptance, understanding and validation not found in many other professional relationships (Mead & McNeil, 2006). By sharing their own lived experience and practical guidance, peer support workers help people to develop their own goals, create strategies for self-empowerment, and take concrete steps towards building fulfilling, self-determined lives for themselves.”

Peer support can be integrated into a wide array of intervention settings relevant to TJC work: in jail-based programming, treatment court settings, and community-based programs and organizations to which people returning from the jail should be connected. In addition to emotional support, peer support workers can provide practical guidance, such as help navigating bureaucratic processes, accessing resources, developing life skills, and building social connections.

System Navigation

People with lived experience can play a critical role working with people returning from jail to engage them in programming and assist them with navigating the various systems they’ll come into contact with. Accessing supports that facilitate reentry success such as Medicaid enrollment can be very technical and confusing, and many people returning from jail have had terrible experiences with legal and social service systems. For these reasons, system navigators with common lived experiences can combine the knowledge of how such processes work, the barriers that are common in the lives of people returning from jail, and the credibility to build trust with reentry clients. They can also bridge the divide between system stakeholders and the community, and open up spaces for more honest conversations around incarceration, reducing stigma, and overcoming resistance to working with people returning home.

Field Example: Transitions Clinic Network Community Health Workers

The Transitions Clinic Network (TCN) works to reverse the harms of mass incarceration and eliminate racial disparities in health and economic well-being. A core component of the work of TCN is hiring and training formerly incarcerated people as community health workers (CHWs). The CHWs work as part of primary care teams. In this role, they engage with people returning from incarceration and work to transform health systems to better serve them.

Research on TCN’s work has found benefits in improving patient health outcomes, access to health care, and reductions in system costs.

Formerly Incarcerated People Engaged in Jail In-Reach

Beginning connections between people with lived experience working in roles such as peer support specialists, system navigators, community health workers and people returning from jail prior to release makes their work more effective. However, local practices around whether people with criminal histories can enter jails to do this work vary. Sheriffs and jail administrators may have considerable discretion regarding allowing facility access, and if they are not permitting such access should explore how to do so, given the evidence of benefit to effectively engaging and supporting reentry clients.

Community Engaged Research Methods

TJC is a data-driven effort, and people with lived experience can play an important role in creating some of that data, complementing administrative data and other sources with insight directly from those experiencing reentry. Community-engaged methods are a rapidly-growing range of approaches that intentionally involve studied communities in the design, execution and interpretation of research results. As an example, San Francisco created an Equity Fellows program to create new collaborative partnerships between system leaders and people with lived experience of incarceration, involving research to generate actionable insights to guide local reform.

Hiring into Staff Positions at All Levels

The section has discussed the various ways that people with lived experience make unique contributions to reentry efforts. It therefore makes sense to have openness to hiring people with lived experience into government and other positions. It is increasingly common to have people with such experience in reentry services positions ranging from frontline staff to agency leadership. Doing this has multiple benefits to a reentry effort, including infusing insights from lived experience throughout reentry work and creating pathways to professional success for people who have returned from jail. Camden County, New Jersey, has built the expectation of working with peers with lived experience into all justice-related program contracts.

Below are some examples of roles individuals with lived experience may fill, and descriptions of how they can uniquely contribute.

- Reentry Case Managers: People with lived experience can bring invaluable first-hand knowledge to case management, helping them to develop individualized plans, connect clients with appropriate services, and advocate for their needs.

- Substance Abuse/Mental Health Counselors: Their personal experiences can give them unique insight into the challenges faced by individuals struggling with addiction or mental health issues, allowing them to offer more effective and empathetic support and counseling. It is important to note that not all individuals with incarceration experience have experience with substance abuse or mental health issues, and vice versa.

- Employment Specialists/Job Coaches: Having faced the barriers of finding employment with a criminal record, individuals with lived experience can effectively help others overcome these challenges by providing job search and interview skills training, resume writing assistance, and connections to potential employers.

- Reentry Program Developers/Trainers: Their real-world understanding of the needs and challenges faced by people transitioning into the community is invaluable in developing effective reentry programs and training curriculum.

- Public Educators/Speakers: Sharing their stories and experiences can raise awareness about the challenges of reentry and the importance of providing support and opportunities for second chances.

In some cases, it may not be possible to hire a person with lived experience for these types of positions. This may be due to state or local laws and regulations, or for other reasons on the part of the individual. However, there are also many volunteer roles people with lived experience can still fill that can be beneficial. Some examples include:

- Support Groups/Mentorship Programs: Sharing their experiences and offering guidance within community support groups or mentorship programs can provide invaluable peer support and encouragement to others going through similar experiences.

- Advocacy & Policy Work: Their firsthand knowledge of the system can empower them to advocate for policy changes that improve reentry outcomes and reduce recidivism.

- Community Outreach & Education: Individuals with lived experience can play a crucial role in educating the public about the realities of incarceration and reentry, helping to break down stigmas and foster understanding.

- Volunteer Mentors in Jails: Sharing their journeys and offering guidance to incarcerated individuals can help them prepare for successful reintegration and inspire hope for change.

Training

It's important to ensure that individuals with lived experience receive proper training and support to effectively fulfill their roles, to continuously deepen and expand their skills and knowledge. For example, education in the form of community college classes, peer support specialist training, and support groups for mentors provide people with lived experience with important career development skills.

Field Examples and Resources

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) makes numerous resources available on peer support.

- La Crosse County OWI Court Policies and Procedures Manual. (2023). La Cross County, WI. This manual discusses the Ambassador Program involving graduates.

- Camden County NuEntry Opportunity Specialist Application (2019).

- Camden County Scope of Work for NuEntry Opportunity Specialist training (n.d.).

- Urban Institute Community-Engaged and Participatory Methods Toolkits (2024).

Module 3: Section 5: Terms Used in the Field

Every field has its own terms and the correctional field is no exception. This section defined a number of basic terms used in this module.

Boundary spanners:

“Individuals who can facilitate communication across agencies and profession to coordinate policies and services.” 1

Efficacy:

The power to produce an effect.

Fidelity:

A measure of the degree to which a given intervention is actually applied or carried out as intended.

Logic model:

“A picture of how your organization does its work—the theory and assumptions underlying the program. A program logic model links outcomes (both short- and long-term) with program activities/processes and the theoretical assumptions/principles of the program.” 2

Long-term public safety:

Differing from simple public safety, which is enhanced for the short term while an individual is incarcerated, long-term public safety involves the prevention of and protection from events that could endanger the safety of the general public, and sustains this desired state over a significant period of time after an individual is released from jail.

Partnership:

“A formal agreement between two or more parties that have agreed to work together in the pursuit of common goals.” 3 Within the criminal justice system, partnership requires that system stakeholders put aside past differences or competition in favor of a mutually agreed upon or shared mission.

Public safety:

The prevention of and protection from events that could endanger the safety of the general public such as crimes or disasters.

Stakeholders:

People, practitioners, or actors within the system of criminal justice as well as those employed outside the system or within the community who share interest in or offer service to transitioning individuals.