Module 5: Targeted Intervention Strategies

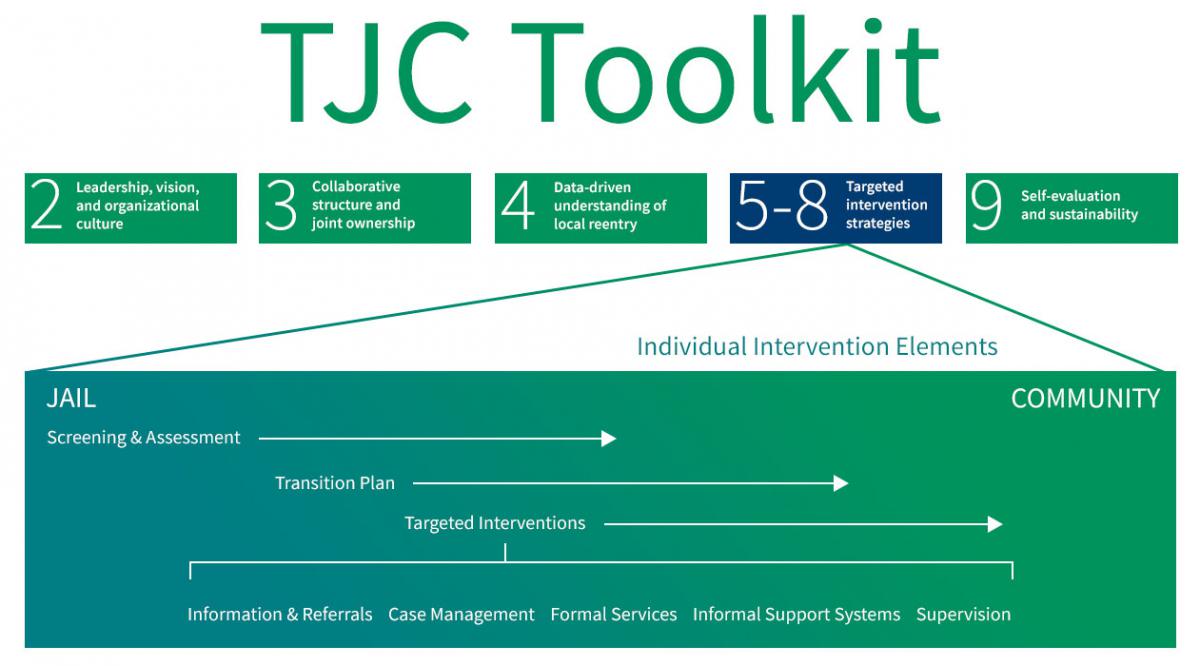

The visual below indicates how Targeted Intervention Strategies are included in the Transition from Jail to Community model. They comprise one of five key system elements that must be in place for the TJC model to work.

Welcome to Targeted Intervention Strategies. This module provides an overview of targeted intervention strategies that are designed to improve the outcomes of people transitioning from jail to the community. This module also will explain how to use the Triage Matrix Implementation Tool to match offenders to the appropriate intervention and how to use the risk-need-responsivity model to increase the likelihood of success for those transitioning from jail to the community.

"Reentry of citizens to our communities is an issue that can and should be addressed beginning within our facilities, from admission all the way through release and assimilation back into our communities. What better time could there be to begin to identify and address the risks and needs of incarcerated individuals than while they are within our care and custody? It is imperative that all of our treatment strategies, both in custody and post release, target and address individual needs consistently to utilize our resources wisely and ensure the best possible long-term public safety outcomes."

Katherine Tilley Burns, Re-entry Coordinator,

Jacksonville Sheriff's Office, Jacksonville, Florida

This module has three sections and should take 10 to 15 minutes to complete.

The recommended audience for this module includes:

|

|

This module also includes resource lists for additional reading.

Module Objectives

This module provides information that will help you to understand why and how targeted intervention strategies form the core of the Transition from Jail to Community (TJC) model at the individual level and comprise the basic building blocks for effective jail-to-community transition.

Improving transition at the individual level involves the introduction of specific interventions targeted by need at critical points along the jail-to-community continuum. The underlying premise, based on an extensive body of research, is that interventions addressing high-risk needs at these key points can facilitate reintegration and reduce reoffending, thereby increasing long-term public safety.

Critical to this approach are the principles that:

- Interventions should begin in jail with the booking process and continue, as needed, throughout incarceration and upon release into the community.

- All interventions should be targeted to the specific needs of each person

- More intensive interventions should be used higher risk people, identified as such through the assessment process, as they often have greater needs and are therefore far more likely to recidivate.

- In-jail interventions and transition services should be offered as available to both sentenced and pre-trial detainees.

This module discusses the:

- Primary elements of targeted intervention strategies.

- Benefits of using targeted intervention strategies to help people transitioning from jail to the community.

- Research that supports the principles underlying targeted intervention strategies.

This module contains the following three sections:

- A Triage Approach to Targeted Interventions

- The Risk-Need-Responsivity Model for Assessment and Rehabilitation

- Terms Used in the Field

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Explain why targeted intervention strategies are needed.

- Complete the Triage Matrix Implementation Tool.

- Identify the key transition intervention strategies of the TJC's Implementation Roadmap.

- Discuss the research that supports targeted intervention strategies.

- Understand the risk-need-responsivity model for assessment and rehabilitation.

Module 5: Principles

Principle 1. Organizational Culture

Effective organizations have well-defined goals, ethical principles, and a history of efficiently responding to issues that have an impact on the outcomes defined by the organizational or system mission. Staff cohesion, support for service training, self-evaluation, and use of outside resources also characterize organizations with a culture that encourages alignment with greater organizational or system goals or objectives.

Principle 2. Program Implementation/Maintenance

Programs and interventions are implemented and maintained to address empirically defined needs of incarcerated people and are consistent with the organization's mission. Programs and interventions are fiscally responsible and congruent with other TJC stakeholder values and missions. All such programs/interventions are designed and implemented after a thorough review of the literature (i.e., meta-analyses) and are consistent with same to ensure that they are evidence-based. Successful local implementations include pilot trials, staff development and maintenance of professional credentials, and program evaluation.

Principle 3. Management/Staff Characteristics

The program director and treatment staff are professionally trained and have experience working with corrections populations. Selection of staff is based on evidence of beliefs that are supportive of rehabilitation, relationship styles, and effective therapeutic skills.

Principle 4. Client Risk/Need Practices

Offender risk is assessed by psychometric instruments of proven predictive validity. The risk instrument includes a wide range of dynamic risk factors, or criminogenic needs (e.g., antisocial attitudes and values). The assessment also takes into account the responsivity of offenders to various styles and modes of service. Changes in risk level over time (e.g., three to six months) are routinely assessed to measure intermediate changes in risk/need levels that may occur as a result of planned interventions.

Principle 5. Program Characteristics

Intensive transition programming aims to change a wide variety of criminogenic needs (factors that predict recidivism) by using empirically valid behavioral, social learning, and cognitive behavioral therapies that are directed toward higher-risk offenders. The ratio of rewards to punishers is at least 4:1. Relapse prevention strategies are available once offenders complete the formal, intensive treatment phase and continue into the community.

Principle 6. Core Correctional Practice

Program therapists engage in the following therapeutic practices: anti-criminal modeling, effective reinforcement and disapproval, problem-solving techniques, structured learning procedures for skill-building, effective use of authority, cognitive self-change, relationship practices, and motivational interviewing.

Principle 7. Inter-Agency Communication

TJC stakeholder agencies make active referrals to one another and advocate for people transitioning from jail to the community to ensure that they continue to receive high-quality services within the community.

Principle 8. Evaluation

TJC stakeholder agencies routinely conduct program audits, consumer satisfaction surveys, process evaluations of criminogenic need changes, and evaluation of outcomes, inclusive of recidivism. Program effectiveness is often evaluated by comparison of recidivism rates of program participants to those of similar risk/need receiving minimal or no treatment.

Module 5: Section 1. A Triage Approach to Targeted Interventions

In this section, you will learn the importance of prioritizing resources and targeting intervention strategies based on system and individual factors. Clearly, given the diversity of the jail population, unpredictable lengths of stay, limited resources, and principles of evidence-based practice, it is not possible or desirable to provide the same level of intervention to everyone who enters the jail setting.

In fact, to obtain an optimum level of efficiency and effectiveness, quick screening tools should be used to separate low-risk offenders from their medium- and high- risk counterparts. The key is to match the right person to the right resources so that higher risk individuals receive more intensive interventions in the jail and the community.

This research-driven practice of targeting the needs of higher risk offenders is often controversial. Many jails and communities tend to “over-program” lower risk offenders and use valuable resources to change their behavior even though intensive programming of lower risk offenders is likely to make them worse rather than better. As a part of such a practice, not only does it make lower risk offenders worse, but valuable treatment opportunities are missed for higher risk offenders who are far more likely to reoffend at a much higher rate and frequency than their lower risk counterparts. Therefore, the TJC project recommends a triage system to help a system determine “who gets what.”

Triage Planning

The word triage comes from the French term “trier,” to sort. We often think of triage scenarios when natural and human disasters occur and decisions have to be made quickly to identify and treat the most seriously injured.

Triage protocols are effective because they: 1

- Bring order to a chaotic situation.

- Quickly sort a large number of people on the basis of a serious condition.

- Set the path for individualized treatment.

- Facilitate a coordinated effort between jail- and community-based supervision agencies and providers.

- Are fluid enough to accommodate changes in the number of people involved in the process, the availability of resources, and the extent of need.

A jail setting is a busy and sometimes chaotic environment, but decisions still must be made at reception to determine each individual's risk and needs. This is a particularly acute problem within a jail facility because of the rapid rate of turnover and short length of stay of most incarcerated individuals. A triage matrix, tailored to the needs, resources, and timelines of your jurisdiction, will help determine the appropriate allocation of services by categorizing individuals and identifying the appropriate mix of targeted interventions.

The following case studies will help you to begin thinking about the unique risk and needs of your population.

Case study 1. Mrs. Thomas is a 42-year-old, married mom of two children awaiting trial and charged with driving under the influence. She is a recovering addict, has one prior felony for drug possession for which she served 180 days in jail, and has been drug free for two years before her most recent relapse. Mrs. Thomas has also worked part-time at a convenience store for the last two years. She does not have a history of failure to appear.

Case study 2. Mr. Banks is a 33-year-old, single male serving a nine-month sentence in the county jail for possession of a half of gram of methamphetamine. Mr. Banks started using drugs when he was 12, dropped out of school in the 11th grade, and served his first prison term at 19 for robbery. He has spent 8 years in prison, the last time before his recent jail stay was for stealing a car while under the influence. At the time of his current arrest, Mr. Banks was unemployed and living in a shelter after losing his construction job for not showing up to work on time.

Case study 3. Mr. Jones is a 19-year-old, single man serving a 15-day sentence for possession of marijuana and medication (Concerta, a stimulant used to treat ADHD) for which he didn't have a prescription. Prior to his arrest, Mr. Jones had no prior criminal record, attended community college, was employed part-time as a waiter at a local eatery and lived with his mother.

Using these three case studies, ask yourself the following questions about these individuals:

- Which screenings and assessment instruments are needed to identify their risk and needs as they enter your facility?

- What are their unique risks?

- What is the likelihood of Mrs. Thomas in case study 1 appearing in court when required?

- How pressing is the need for intervention?

- How extensive is the need for intervention?

- What is the likelihood of reoffending and how severe might the crime be?

- What are their unique needs?

- Do you know their length of stay?

- What factors would you use to sort them by risk and needs?

- What type of jail and community intervention is required?

- What type of transition planning and which specific targeted interventions, if any, are needed?

Don't worry if you don't have all the answers. In this module and the next three modules, you will learn how to perform the following 11 tasks (outlined in the Targeted Intervention Strategies section of the TJC Implementation Roadmap) and designed to address these and related topics:

- Complete the Triage Matrix Implementation Tool .

- Apply screening instruments to all jail entrants.

- Apply risk/needs assessment instrument(s) to selected higher risk jail entrants.

- Produce transition case plans for jail entrants according to risk and need.

- Develop pretrial practices to support jail transition and/or community supervision as applicable.

- Define scope and content of jail transition interventions currently in place.

- Provide resource packets to all jailed individuals upon release.

- Deliver in-jail intensive interventions to selected higher risk jailed individuals and other specific interventions to address the needs of medium or lower risk individuals who are afflicted with a specific ailment or condition such as opiate addiction or mental illness.

- Deliver community interventions to released individuals according to and with continuity to interventions or treatment received while incarcerated.

- Provide case management for criminally involved people according to risk and need in both incarcerated settings and within the community upon release.

- Provide mentors as applicable to assist people transitioning from jail to the community.

To begin, review The Triage Matrix Implementation Tool referenced in Task 1 and developed by the TJC project team to help your jurisdiction prioritize goals, identify target populations, and allocate limited resources to your jurisdiction's intervention strategies. The underlying concept is that everyone in the jail population should get some intervention, which may be as minimal as receiving basic information on community resources, but the most intensive interventions are reserved for incarcerated individuals with higher risk and needs. The triage matrix includes the following four sections:

- Screening and Assessment

- Transition Case Plan

- Pre-Release Interventions

- Post-Release Interventions

The triage matrix includes a worksheet for each section and a sample matrix with all sections completed. All content in the sample triage matrix is approximate and should be adapted to fit your community. We recommend that you fill in the triage matrix as soon as possible to better understand the strengths and gaps in your present transition system.

1 United States Army, Office of the Division Surgeon, 10th Mountain Division. (n.d.). Presentation delivered as part of a trauma-focused training. Fort Drum, NY.

2 Fretz, R. (2006). What makes a correctional treatment program effective: Do the risk, need, and responsivity principles (RNR) make a difference in reducing recidivism? Kearney, N.J.: Community Education Centers, Inc.

Section 1: Resources

- Bogue, B., Campbell, N., Carey, M., Clawson, E., Faust, D., Florio, K., Joplin, L., Keiser, G., Wasson, B., & Woodward, W. (2004). Implementing evidence-based practice in community corrections: The principles of effective intervention . National Institute of Corrections.

- Christensen, G. (2008, January). Our system of corrections: Do jails play a role in improving offender outcomes? Crime and Justice Institute and the National Institute of Corrections.

- Dunworth, T., Hannaway, J., Holahan, J., & Turner, M. A. (2008). Beyond ideology, politics, and guesswork: The case for evidence-based policy . The Urban Institute.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration. (2007, October). A guide to evidence-based practices on the web. (THIS IS NO LONGER AVAILABLE)

Summary

Now that you have completed this section, you should understand that incarcerated people have varying needs. Some require intensive interventions, while others require little or no intervention. The Triage Matrix Implementation Tool and the TJC Implementation Roadmap can help you prioritize goals, identify and target specific populations for appropriate interventions, and allocate resources efficiently and effectively.

Module 5: Section 2. The Risk-Need-Responsivity Model for Assessment and Rehabilitation

Latessa and his colleagues identify eight principles of effective correctional intervention. They are included here so you can better understand how to increase the chance of successful intervention. Tools such as the Correctional Program Assessment Inventory (CPAI) are available to determine the extent to which your strategy meets these principles .

Principle 1. Organizational Culture

Principle 2. Program Implementation/Maintenance

Principle 3. Management/Staff Characteristics

Principle 4. Client Risk/Need Practices

Principle 5. Program Characteristics

Principle 6. Core Correctional Practice

Principle 7. Inter-Agency Communication

Principle 8. Evaluation

From Latessa, E. J., Cullen, F. T., & Gendreau, P. (2002). Beyond correctional quackery—Professionalism and the possibility of effective treatment. Federal Probation, 66(2), 43–49.

In the last section, we frequently used the terms risk and needs. In this section, you will learn the research behind the risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model and why this model is an important concept to understand when carrying out the 10 tasks outlined in the Targeted Intervention Strategies section of the TJC Implementation Roadmap.

Risk-Need-Responsivity Model

Researchers have spent years formulating the principles of effective intervention strategies for correctional populations. Many researchers support the risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model, which states that the risk and needs of the incarcerated individual should determine the strategies appropriate for addressing the individual's criminogenic factors before and after release.

According to Don Andrews and James Bonta, leading criminal justice scholars, the RNR model is based on the following three principles: 1

1. Risk principle. Match the level of service to the offender's risk of reoffending, based on static factors (e.g., age at first arrest, history of arrest, current age) and dynamic factors (e.g., substance abuse, antisocial attitudes). Higher-risk offenders should receive more intensive intervention.

2. Need principle. Assess criminogenic needs and target them in treatment. High-risk offenders should receive intensive treatment, while low-risk offenders should receive minimal or no treatment.

3. Responsivity principle. Maximize the offender's ability to learn from a rehabilitative intervention by providing cognitive behavioral treatment and tailoring the intervention to the learning style, motivation, abilities, and strengths of the offender.

Criminologist Edward Latessa believes that programming focused on cognitive behavioral therapy is the most effective way to treat criminogenic needs. As he states, “Thinking and behavior are linked: offenders behave like criminals because they think like criminals; changing thinking is the first step towards changing behavior.” 3

Risk:

The probability that an offender will commit additional offenses

Criminogenic Need:

Factors that research has shown have a direct link to offending and can be changed.

Responsivity:

Matching an offender's personality and learning style with appropriate program settings and approaches

Criminogenic needs are dynamic (changeable) risk factors that are proven through research to affect recidivism. These factors include: 2

- Antisocial values, beliefs, and cognitive-emotional states.

- Rage, anger, defiance, criminal identity.

- Antisocial friends.

- Isolation from prosocial others.

- Substance abuse.

- Lack of empathy.

- Impulsive behavior.

- Family dysfunction, such as criminality, psychological problems, abuse, neglect.

- Low levels of personal education.

Research shows women enter the criminal legal system differently and at a different frequency compared to their male counterparts. Women typically are charged with different types of offenses, and have different mental health and substance use issues, histories of victimization and sexual violence, parenting responsibilities, and experiences of poverty. In addition, women are more likely to report experiencing physical and sexual abuse in their lifetimes, and for longer periods of time compared to men. This increases trauma and affects needs under correctional supervision. In jails, women are more likely to die than men, with drug and alcohol intoxication being the cause of death twice as often for women.

What we know is that differences between the lives of men and women can shape their patterns of criminal behavior and create prevalent “pathways” to crime. While there is not one primary pathway for women, the following factors contribute to criminal legal system involvement:

- Experiences of abuse or trauma

- Poverty and marginalization

- Mental health issues

- Substance abuse

- Relationship issues

National statistics indicate that over 1.2 million women were admitted to jails in 2021, marking a 22% increase from 2020. 60% of women in jail have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial. Women of color enter jails more than white women. It is estimated that approximately two-thirds of women in jail are women of color (44% Black, 15% Hispanic, and 5% were of other racial/ethnic backgrounds) compared to 36% of women in jail who are white. 80% of women in jails are mothers, and most are often the primary caretakers of their children. As women continue to be the fastest growing jail population, an understanding of responsive approaches is critical to ensure the distinct needs of women are considered in practices and programs. Understanding the differences in offending histories, risk factors, and trauma experienced by women can allow your jail to better address the needs of women and tailor programs to meet the unique needs of women as they transition back into the community. The TJC Toolkit will include specific guidance on applying responsive principles for women in modules 6, 7, and 8.

TJC Leadership Profile

Click here for a TJC Leadership Profile on Gevonnia Thurman, Correctional Officer, Thinking for a Change Instructor in Jacksonville, Florida.

Risk relates to the actual and perceived threats that people released from jail pose to the safety and property of potential victims in the community. 4 Imagine such risks as being on a continuum: At one end are people who incarcerated because they are too dangerous to be safely managed in the community and at the other end are people charged with a criminal offense who pose little or no risk to public safety.

When determining where a person falls on the continuum (risk assessment), you need to consider a number of factors (criminogenic needs) that research has shown are associated with recidivism. These criminogenic needs are dynamic, in that they can change over time. 5 Ensuring that higher risk people returning to the community have accessed and will continue to access partnership services that address criminogenic needs is critical for managing and reducing potential risks they may pose to the community.

1 Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2007). Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation . Public Safety Canada.

2 Latessa, E. J., Cullen, F. T., & Gendreau, P. (2002). Beyond correctional quackery: professionalism and the possibility of effective treatment .” Federal Probation 66(2): 43-49.

3 Chapman, T. & Hough, M. (1998). Evidence-based practice: A guide to effective practice . London: Home Office Publications Unit.

4 Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, Intensive program prisons web page .

Section 2: Resources

1. Fretz, R. (2006). What makes a correctional treatment program effective: Do the risk, need, and responsivity principles (RNR) make a difference in reducing recidivism? This article describes the risk-needs-responsivity model, and the importance of generating a treatment environment.

2. Grattet, R., Jannetta, J., & Lin, J. (2006). Evidence-based practice in corrections: A training manual for the California Program Assessment Process (CPAP). University of California, Irvine: Center for Evidence-Based Corrections.

3. Kajstura, A. & Sawyer, W. (2024). Women’s mass incarceration: The whole pie 2024. Prison Policy Initiative.

4. Lynch, S. M., DeHart, D. D., Belknap, J., & Green, B. L. (2012). Women's pathways to jail: The roles & intersections of serious mental illness & trauma. Bureau of Justice Assistance.

5. National Institute of Corrections. (2024). Evidence-based practices (EBP) topic categories and resources

6. National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women. An online resource for professionals, policymakers, and practitioners who work with adult women involved in the criminal justice system.

7. Ramirez, R. (n.d.). Reentry considerations for justice involved women. National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women,

8. Scott, Wayne. (2008). Effective clinical practices in treating clients in the criminal justice system. Crime and Justice Institute.

9. Sawyer, W. & Bertram, W. (2022). Prisons and jails will separate millions of mothers from their children in 2022. Prison Policy Initiative.

10. Swavola, E., Riley, K., & Subramanian, R. (2016). Overlooked: Women and jails in an era of reform. Vera Institute of Justice

11. Wang, L. (2021). Rise in jail deaths in especially troubling as jail populations become more rural and more female. Prison Policy Initiative.

12. Zeng, Z. (2022). Jail inmates in 2021 – Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Summary

Now that you have completed this section, you should understand the basis for effective practices central to the TJC model. By accurately assessing risk, you can determine the most appropriate treatment interventions for various justice involved individuals. You should understand that only needs that are directly related to offending should be the subject of interventions. Interventions should be responsive to individual learning style, motivation, abilities, and strengths.

Module 5: Section 3: Pretrial Interventions

In many jurisdictions the concept of Targeted Intervention Strategies is synonymous with working with the sentenced population. When asked why this is the case, the two most reoccurring jurisdictional responses are:

- Not enough time and resources to work with pretrial detainees before they are released.

- Community safety issues with pretrial release.

In this section, we will highlight the importance of incorporating the pretrial population into your TJC work. First, we will outline some important pretrial population facts, then identify the benefits of targeting pretrial detention for TJC practices and finally, demonstrate that community safety is not put at risk when pretrial detention alternatives are implemented properly.

The facts speak for themselves. The large majority of people in jail are detained pretrial. Many defendants spend a lot of time in jail throughout the pretrial period. Often times by the time they have plead guilty they have either sat in jail for so long they have served their time and are released, or have only a few weeks left on their sentence to serve.

In many jails comprehensive treatment interventions are reserved for the sentenced population, so the opportunity for many defendants to receive in-jail services is lost because the entire or majority of their sentence is served during the pretrial period.

The Solution

The laws in most jurisdictions require courts to release defendants under the least restrictive conditions necessary to reasonably assure public safety and court appearance. Validated pretrial risk assessment tools are in use in many jurisdictions that successfully sort defendants into categories showing their risks to public safety and of failure to appear in court. By using these tools, jurisdictions can match appropriate pretrial release conditions to the identified risk levels of each defendant, and help judges to assure that only those with unmanageable risks remain in jail pending trial.

Jails benefit from this practice since it relieves overcrowding, saves valuable resources that can be allocated for interventions targeted for pretrial and sentenced individuals who present a higher public safety risk

Lower risk defendants benefit by returning to their jobs, families, and communities where they can receive the support and treatment services they often need while maintaining prosocial commitments and relationships.

Is Pretrial Release Safe for the Community?

Empirical research continues to demonstrate that most defendants appear in court as required and are not rearrested on new charges while on pretrial release. Even those defendants who score in the highest risk level in validated pretrial risk assessments often appear in court and remain arrest-free while their cases are pending. For example, research in Virginia shows that over 80 percent of defendants overall and around 60 percent in the highest risk category make all their court appearances, and over 75 percent overall and 55 percent in the highest risk category have no rearrests. [1] Similarly, in Cook County after bail reform changes 80 percent of people released pretrial made all of their court appearances, and only 17 percent had a new arrest during the pretrial release period. [2] Further, research in Kentucky found that any period of pretrial detention longer than 23 hours was associated with greater likelihood of rearrest, [3] elevating the importance of avoiding unnecessary pretrial detention. It is because of these and similar findings that the Conference of Chief Justices, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, the National Sheriffs’ Association, and the American Jail Association, among others, have all called for the use of evidence-based pretrial risk assessment tools to help judges identify the small minority of defendants who pose too great a risk to be released.

Resources

Pretrial Justice Institute. (2010). Pretrial services program implementation: A starter kit . Pretrial Justice Institute.

Stemen, D. & Olson, D. (2020). Dollars and sense in Cook County: Examining the impact of general order 18.8A on felony bond court decisions, pretrial release, and crime . Loyola University, Chicago.

Vetter, S. & Clark, J. (2012). The delivery of pretrial justice in rural areas: A guide for rural county officials. National Association of Counties.

Summary

Now that you have completed this section, you should understand the pretrial defendants make up the majority of the jail population. Many of them are incarcerated because they do not have the money to attain a bond or post bail that have been set by the court, and not because of their risk to the community or their failure to appear in court if released. Using evidence-based pretrial risk release instruments will help jurisdictions determine which detainees are good candidates to return to their community pending their court date.

Module 5: Section 4: Increasing Connections to Behavioral Health Care Before Leaving Jail and During Reentry

It’s a well-known fact that people with behavioral health needs (see Box 1) are overrepresented in American jails. An estimated 44% of people in jail have a mental illness , and 63% have a substance use disorder . Unfortunately, it is also true that most jails were not designed to manage people with severe mental illness nor are they equipped to do so. Despite these realities, jails have become the de facto mental health institution of most of our communities. This is problematic for many reasons, most notably because incarceration often exacerbates symptoms for people with behavioral health needs, making reentry into the community potentially more challenging.

This module is using the American Medical Association definition of “behavioral health” which refers to both “mental health and substance use disorders”. As such, “behavioral healthcare” refers to “the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of those conditions” as well. It should be noted that mental health disorders and substance use disorders are not the same and have different corresponding diagnoses and treatment options. However, both types of disorders require assessment, care coordination, and treatment plans, so we are discussing both together within this module.

One of the biggest barriers people with behavioral health needs face upon release is poor connection with community behavioral healthcare providers. Addressing this issue is a key component of any targeted intervention strategy and is instrumental in promoting successful reentry, reducing the likelihood of re-incarceration, and increasing connections to necessary treatment and services. This module outlines 8 steps that jail staff and corrections-based treatment providers can take to ensure successful behavioral health care in jail, as well as continuity of care upon release (see box below for what is not covered in this module).

This module does not address suicide prevention or overdose and withdrawal management. Although these issues are extremely important to address due to their increasing prevalence in jail settings, this module focuses on behavioral health care in reentry planning and utilizing the available resources to facilitate success after release from incarceration. This is simply because providing overdose and suicide prevention programming guidance within jails is beyond the scope of this toolkit, which is focused primarily on improving reentry processes. For more information, please refer to the National Institute of Corrections resources on suicide prevention and managing substance withdrawal in jails.

Step 1: Identify people with behavioral health needs before they leave jail and develop a treatment plan for use in the community.

As discussed in Module 6, jails should use a validated behavioral health screening tool at booking into jail to help to identify who to refer for a clinical assessment and potential behavioral health disorder diagnosis. For those who are diagnosed with a behavioral health disorder, a treatment plan must be developed and communicated to behavioral health treatment providers who are available in the jail. Although short and unpredictable periods of incarceration and staffing shortages may make this process more difficult, it is necessary to provide everyone diagnosed with a behavioral health disorder the following:

- A transition plan; and

- A referral to—and when possible, an appointment with— a community-based treatment provider who has experience serving people with their specific behavioral health needs.

If possible, provide the following:

- A warm handoff, where the treatment provider meets with the individual prior to release from jail or the person can be transported directly to the community treatment provider from jail.

- Prescriptions for any current behavioral healthcare-related medication the individual is using and a short supply of the medication to take with them into the community.

- Coordinated system wide planning entities to develop mechanisms for criminal justice system stakeholders and behavioral health system stakeholders to communicate regularly with each other around case planning.

Step 2: Identify who had previously received behavioral healthcare services in the community prior to coming to jail.

“People with serious mental illnesses and complex needs don’t often get better by going to jail.”

-Regi Huerter, Policy Research Associates

Continuity of care is just as important at intake as it is during reentry. Communication and transparency between the jail and the community providers is essential to arranging a smooth transition of care. Appropriate jail staff need to know who in their jail is receiving community-based behavioral health services and the providers must also be aware of when their patients are booked into jail. At release, everyone should receive a detailed record of treatment and medication during their jail stay and treatment providers should have access to that information as they plan to provide services immediately upon release from incarceration.

To achieve this goal, some communities have developed integrated county behavioral health and criminal legal data systems to share this information automatically. For example, in Camden County, NJ, the jail’s management system interfaces with the Camden Coalition’s Health Information Exchange (HIE). Key healthcare data regarding an individual in the jail is matched with their record in the HIE. This enables both the outside health system providers to see the history of treatment while the person is incarcerated and the jail medical team is able to see a person’s medical history before being booked into the facility.

Other jurisdictions, like Pima County, Arizona, have allowed behavioral health providers to cross-check the daily “roster” of who is booked into the local jail with their patient list to see if transition of care is needed. While the level and process of information sharing will look different from county to county, the most basic level of information sharing is necessary to allow for a person with behavioral health needs to maintain treatment while incarcerated and be re-connected to their service provider upon release.

Step 3: Establish collaboration between jail staff and behavioral healthcare providers to improve healthcare access, community safety, and individual behavioral health outcomes.

Information sharing is just one part of the collaboration between jail staff and community behavioral health providers that’s necessary for care coordination during transitions to and from incarceration. Other examples of collaboration include:

(1) Treatment planning,

(2) Clarifying roles and responsibilities,

(3) Making sure treatment, and supervision efforts are complementary (for those on community supervision), and

(4) Transitioning people to treatment without a lapse in care.

We recommend regular meetings where corrections staff, behavioral health providers (jail- or community-based), case managers, and/or community corrections staff come together to create and discuss personalized care plans for addressing behavioral health needs. Don’t forget to include peer mentoring agencies that provide peer support for jail-based clients as their work is so important for successful outcomes.

In Hillsborough County, NH the jail superintendent and program staff meet with all behavioral health providers to include MOUs and plans for both in-reach services and community-based referral. This has resulted in two federal grants that have enhanced both mental health and MAT services in the jail and at transition back to the community.

No matter how this collaboration is achieved, regular cross-agency partnership, support, and communication is necessary for successful transition care coordination.

Step 4: Ensure people leaving jail have health insurance in tandem with care coordination.

Access to health insurance is essential for receiving treatment in the community. Jails can help ensure that people leaving jail have health insurance by facilitating the enrollment process during release. Various jurisdictions employ the following practices to accomplish this purpose:

(1) Provide information and assistance on applying for Medicaid or other health insurance programs and , if allowable, connect people to Medicaid while in jail.

(2) Collaborate with community health agencies so they can offer support when navigating the enrollment process.

(3) Have jail staff connect people with organizations or advocates that specialize in assisting recently released individuals with accessing health insurance.

(4) Hire navigators either at the facility or based in the community who work to ensure the individual has insurance at the time of transition from jail. (See Box 3).

Remember, however, that, insurance alone is not enough to guarantee access to care or the appropriate level of care. Care coordination efforts are necessary in tandem with health insurance enrollment to make sure appropriate treatment plans are developed and implemented in the community, as discussed in previous steps.

Since 1965, the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy has prohibited Medicaid from covering incarcerated individuals, barring inpatient services. However, this convention may be changing. Recently, some states have received approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for a Section 1115 waiver, which will allow Medicaid, for the first time, to cover services for certain groups of incarcerated people – including those in jail – up to 90 days prior to their release date. Now, some behavioral health treatment services can be reimbursed while people are in jail, which will create further demand for enrolling people in health insurance as soon as possible. This means that there will be a greater need than ever for comprehensive care plans to transition treatment from incarceration to a community setting.

Step 5: Take into account any relevant legal considerations.

The previous steps mostly focused on considerations related to the behavioral health needs of incarcerated individuals, but there are often legal considerations to be aware of when planning transition of care. Jail staff should ask partner agencies for any legal information (like court dates and conditions of supervision) that might impact a person with behavioral health needs, such as their terms and conditions of release, court participation requirements, supervision plans, and treatment approaches. This information should be included in case management and reentry plans so treatment providers can help to support reentry candidates while ensuring that they meet any legal obligations, such as appearing in court and attending mandated community treatment or supervision.

Step 6: Transition care to aligned evidence-based programs.

When leaving jail, people with behavioral health needs should be referred to tailored evidence-based programs and practices designed for their specific behavioral health needs. For example, people diagnosed with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders (COD) should receive integrated treatment designed for people with COD. Whenever possible the process of referral should begin as soon as possible and working with agencies to fast track clients at the point of transition to the community. In some communities, behavioral health agencies have a 2-3 month waiting list to enter treatment, demonstrating the need for early referrals.

Where appropriate, these evidence-based programs should be adapted to specifically address the eight criminogenic risk factors, as discussed in Module 5, that have the strongest associations with “criminal behavior”: (1) history of antisocial behavior; (2) antisocial personality traits; (3) antisocial cognition; (4) antisocial associates; (5) family and/or marital strain; (6) problems at school and/or work; (7) problems with leisure and/or recreational time; and (8) substance use. Criminogenic risk factors vary for women. Programming that is responsive to women should address the following risk factors: (1) child abuse and adversity; (2) intimate partner violence; (3) traumatic brain injury; (4) mental health and substance use disorders; (5) failure-to-protect laws; (6) sex work.

Following the “responsivity” component of the “Risks-Need-Responsivity” model, treatment should be specific and appropriate for the individual needs of the client, which could include cognitive-skills training that focuses on judgment, criminal behaviors, motivation, problem solving, skill building, and that assists in building prosocial supports and activities. Simply referring people to a behavioral health treatment provider is not enough; they should be connected to a treatment provider who provides evidence-based interventions designed to address that person’s particular behavioral needs.

A medication-assisted treatment (MAT) program combines FDA-approved medications with behavioral therapy can be crucial for successful reentry for individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD). Not only does it reduce craving and relapse risk, but it can help manage co-occurring mental health issues, facilitate behavioral therapy engagement, and reduce recidivism. More and more jails are implementing MAT programs successfully . Franklin County, Sheriff’s Office, MA (FSCO) began their MAT program in 2016 and has seen a significant reduction in recidivism among program participants.

Step 7: Develop responses that recognize disparities in the criminal legal and behavioral health systems.

Some individuals, those with low economic status, and LGBTQ+ individuals often face unequal access to quality behavioral health treatment and are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. It is important for jail staff, reentry coordinators, and community providers to be aware of these structural disparities, and of the biases they may bring into their work that can interfere with effective treatment and perpetuate these disparities. While women aren’t overrepresented in the criminal legal system, they are the fastest growing incarcerated population and they often have different behavioral health needs than men. When transitioning care, reentry planners should identify responsive behavioral health treatment options.

Step 8: Engage the person in need of services, and their family, directly in treatment planning.

While clinical professionals should make the ultimate decision about treating someone with a behavioral health disorder, it’s important to involve the individual leaving jail in this process. The person being referred to treatment should have a say on what types of treatment they need, who they want as their provider, and where they’d like to receive their treatment. One study found that people leaving incarceration had different ideas about the health services they needed compared to what the treatment providers in corrections suggested, especially for substance use treatment. To mitigate this, case managers should directly ask the person leaving jail what factors they should keep in mind when making referrals, such as transportation needs, timeframe for treatment, and location.

Additionally, case managers should be engaging family members, friends, and loved ones as much as possible prior to, and during the reentry process. A lack of family and social support is negatively impactful for all people reentering the community from incarceration, and has even greater negative effect on those with behavioral health disorders. Engaging family in the treatment planning process can be a critical; for disrupted relationships with family members and loved ones can result in isolation and lead to worsened mental health and an increased likelihood of reincarceration. For those with substance use needs, social isolation can often lead directly to relapse, especially early in the reentry process.

More Information and examples from the field:

- Beeler, S., Renn, T., & Pettus, C. (2023). “…he’s going to be facing the same things that he faced prior to being locked up”: Perceptions of service needs for substance use disorders. Health Justice, 11(1), 13

- Bronson, J., & Berzofsky, M. (2017). Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics .

- Bronson, J., Stroop, J., Zimmer, S., & Berzofsky, M. (2017). Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007-2009: Special report .Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice.

- Bureau of Justice Assistance. (2022).Cognitive behavioral therapy at the intersection of criminal behavior and substance use disorder. U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs.

- Camden County, NJ Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Program (COAP) Flowchart for referrals

- Hillsborough County (NH) Department of Corrections. (2023). Accept and Commit to Treatment (ACT) program participant handbook.

- Hillsborough County (NH) Department of Corrections. (2023).Policy and procedure manual for ACT HCDOC substance abuse program.

- Kendall, S., Redshaw, S., Ward, S., Wayland, S., & Sullivan, E. (2018). Systematic review of qualitative evaluations of reentry programs addressing problematic drug use and mental health disorders amongst people transitioning from prison to communities. Health Justice, 6(1), 4.

- Mallik-Kane, K., Paddock, S. M., & Jannetta, J. (2018). Health care after incarceration: How do formerly incarcerated men choose where and when to access physical and behavioral health services? Urban Institute.

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care, Jail-Based MAT: Promising Practices, Guidelines and Resources.

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) and American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP).(2020). Suicide prevention resource guide: National response plan for suicide prevention in corrections. NCCHC.

- Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. (2021, October 7). Nearly a fifth of state and federal prisons and a tenth of local jails had at least one suicide in 2019 [Press release].

- Ramezani, N., Breno, A. J., Mackey, B. J., Viglione, J., Cuellar, A. E., Johnson, J. E., Taxman, F. S. (2022). The relationship between community public health, behavioral health service accessibility, and mass incarceration. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 966.

- SAMHSA. (2024). The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM). This is an approach to understanding how individuals with mental and substance use disorders come into contact with and move through the criminal justice, to identify resources and gaps.

- Swanson J. (2016). Mental illness, release from prison, and social context. JAMA.

- The National Council for Mental Wellbeing and Vital Strategies. (2020). Medication-Assisted Treatment for opioid use disorder in jails and prisons: A planning and implementation toolkit. The National Council.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance & National Institute of Corrections (2023). Guidelines for managing substance withdrawal in jails: A tool for local government officials, jail administrators, correctional officers, and health care professionals. Authors.

- Wishner, J. B., & Mallik-Kane, K. (2017, February 3). Information sharing between Medicaid and corrections systems to enroll the justice-involved population: Arizona and Washington. Urban Institute.

Summary

In this section, you learned how to formalize a structure for identifying a person’s behavioral health needs and connecting them to treatment in the community. We also identified steps criminal legal system agencies should take to ensure connection to care for people with behavioral health disorders, prior to and upon transition from jail to the community.

Module 5: Section 5. Terms Used in the Field

This section defined basic terms used in this module. These terms have been highlighted throughout the module, allowing you to rollover the term to see the definition.

Assessment

The systematic collection, analysis, and utilization of objective information about an offender's level of risk and need.

Cognitive behavioral process

The complex relationship among thoughts, feelings, and behavior. People learn to manage this relationship from personal experience and from interaction with significant others. Deficits in the cognitive behavioral process may reinforce antisocial behavior, and these deficits often can be corrected through cognitive behavioral therapy. 2

Criminogenic factors

Recognized factors that have been proven to correlate highly with future criminal behavior.

Criminogenic needs

Factors that research has shown have a direct link to offending and can be changed.

Effective practice

Modes of operation that produce intended results, 3 and, in relation to the TJC model, that enable the successful community reintegration of offenders so they end up leading productive and crime-free lives.

Evidence based practice

The conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual offenders by integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. 4

Modeling

Within a social-learning environment, the demonstration of pro-social skills by correctional officers, staff, and counselors to reinforce positive changes exhibited by transitioning offenders. An all-important aspect of any transition effort because successful transition efforts have been proven to take place within social-learning environments.

Responsivity

Matching an offender's personality and learning style with appropriate program settings and approaches. 5

Risk

The probability that an offender will commit additional offenses. 6

Triage

The process by which a person is screened and assessed immediately on arrival at the jail or community service to determine the urgency of the person's risk and needs to designate appropriate resources to care for the identified problems. 7

1 Zajac, G. (2007). Principles of effective offender intervention . Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, Office of Planning, Research, Statistics & Grants.

2 Chapman, T., & Hough, M. (1998). Evidence-based practice: A guide to effective practice . Home Office Publications Unit.

3 Ibid.

4 Adapted from Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M. C., Gray, J. A. M., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn't. British Medical Journal, 312 (7023), 71–72.

5 Zajac, G. (2007). Principles of effective offender intervention . Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, Office of Planning, Research, Statistics & Grants.

6 Ibid.

7 Cook, S., & Sinclair, D. (1997). Emergency department triage: A program assessment using the tools of continuous quality improvement. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 15(6), 889–894.

[1] Virginia Sentencing Commission. (2023).Virginia pretrial data project: Findings from the 2019 and 2020 cohorts. Virginia Sentencing Commission.

[2] Stemen, D. & Olson, D. (2020). Dollars and sense in Cook County: Examining the impact of general order 18.8A on felony bond court decisions, pretrial release, and crime. Loyola University, Chicago.

[3] Lowenkamp, C.T. (2022). The hidden costs of pretrial detention revisited . Arnold Ventures.